Was Wittgenstein a Mystic?

If you bring together two enigmas, do you get a bigger enigma, or do they cancel each other out, like multiplied negative numbers, to produce clarity? The latter, I hope, as I take on Wittgenstein and mysticism.

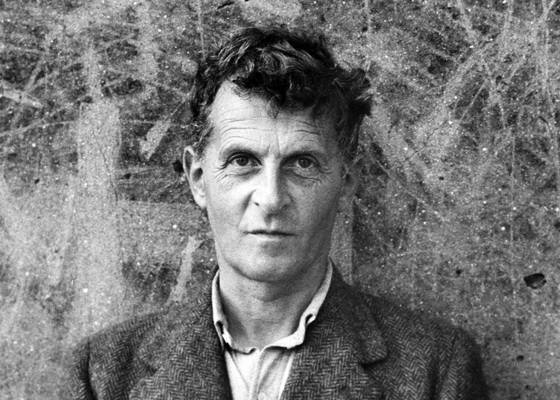

I’ve been puzzling over these topics since my philosophy salon met to discuss “The Mysticism of the Tractatus,” written in 1966 by B.F. McGuinness. The salon consists of eight or so people, most with graduate degrees in philosophy, who gather in the salon-runner’s living room to jaw over a paper. Ludwig Wittgenstein, whom Bertrand Russell described as “the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived,” published only one book during his lifetime, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. First issued in German in 1921, Tractatus is a cryptic meditation on what is knowable and unknowable.

“Mysticism” is often used as a derogatory term to describe obscure, fuzzy thinking, or woo. But in “The Mysticism of the Tractatus,” McGuiness uses the term to refer to an extraordinary form of perception described by sages east and west. In Varieties of Religious Experience, still the best scholarly treatment of mysticism, William James notes that during a mystical experience you feel as though you are encountering absolute truth, the ground of being, God. These revelations are laden with spiritual significance and accompanied by intense emotions. You often feel a sense of blissful timelessness and oneness with everything (although the experience can also be hellish).

The knowledge imparted by the vision seems to transcend philosophy, science and reason itself. James calls mystical experiences ineffable, which means that they cannot be expressed in ordinary language. The author of the mystical ancient Chinese text Tao Te Ching expressed this idea when he wrote, “Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.” The author violates the rule in stating it.

The Tao Te Ching and other mystical tracts seethe with these sorts of Godelian, “this-sentence-is-false” paradoxes, and so does Tractatus. Wittgenstein writes, “Not how the world is the mystical, but that it is.” He elaborates: “We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Of course there is then no question left, and just this is the answer. The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem.” Even when the world has been thoroughly explained by science, Wittgenstein seems to be saying, it hasn’t really been explained at all. The answer to the riddle of life is that there is no answer.

In his 1966 paper, McGuiness notes that in a “Lecture on Ethics” published after his death in 1951, Wittgenstein described personal experiences with mystical overtones. In one he felt “absolutely safe” and “in the hands of God.” In another he was filled with astonishment at existence and saw “the world as a miracle.”

McGuinness explores analogies between Wittgenstein’s experiences and ones described by James, the philosopher Schopenhauer, the Catholic monk Meister Eckhart and the Muslim sage al-Qushayri. McGuiness also mentions Aldous Huxley, whose Doors of Perception describes mystical experience induced by mescaline. As I mention in my book Rational Mysticism, Huxley and psychedelics were formative influences on me.

Bertrand Russell, who was fascinated by both Wittgenstein and mysticism, described Wittgenstein as a mystic. In a letter to a friend in 1919 Russell wrote:

[Wittgenstein] seriously contemplates becoming a monk. It all started from William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience, and grew (not unnaturally) during the winter he spent alone in Norway before the war, when he was nearly mad. Then during the war a curious thing happened. He went on duty to the town of Tarnov in Galicia, and happened to come upon a bookshop, which, however, seemed to contain nothing but picture postcards. However, he went inside and found that it contained just one book: Tolstoy on the Gospels… He has penetrated deep into mystical ways of thought and feeling, but I think (though he wouldn’t agree) that what he likes best in mysticism is its power to make him stop thinking.

I like that final sardonic twist. I found this quote from Russell in a 2009 essay on Wittgenstein’s mysticism by philosopher Russell Nieli. Nieli warns that most philosophical commentary on Tractatus “has focused on the book’s technical system of logic and language with little concern for its overarching moral and spiritual thematic.” Tractatus “remains misunderstood largely because of interpreters’ failure to appreciate the importance of the mystical and the ecstatic as they are interwoven into the text.”

For a similar reading, see “Understanding the Mysticism of Wittgenstein’sTractatus,” an essay on the website EPISTEMIC EPISTLES. The writer asserts that “properly understanding Wittgenstein’s intention in the Tractatus requires conceiving of the Tractatus as a mystical project, intended to acquaint us with mystical experience, rather than an attempt to communicate analytic ‘truths’.” Failure to recognize Wittgenstein’s mystical intentions results in “a misconceived superficial reading.”

The problem is, if you haven’t had a mystical experience, mystical writings seem like, well, woo. Based on their reactions to McGuiness’s paper “The Mysticism of the Tractatus,” the philosophers in my salon haven’t had mystical experiences. They read Tractatus as an extreme, idiosyncratic expression of logical positivism, a philosophical school, popular in the early 20th century, that imposes strict constraints on what is knowable. My salon mates expressed puzzlement and even disdain for the “incoherent” and “juvenile” (their words) mystical elements of Tractatus. They noted that Wittgenstein distanced himself from Tractatus in his later work Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously).

I felt like blurting out, Haven’t you ever dropped acid? Haven’t you ever been overcome by the weirdness of the world? To my mind, Tractatus is best viewed as a work of negative theology. This mystical branch of theology begins with the premise that God transcends understanding and description. Tractatus recalls the negative theology of Lao Tzu, Eckhart, Saint Theresa and the 6th-century monk Pseudo-Dionysius. The latter once wrote (and I found this passage in Nieli):

The higher we soar in contemplation the more limited become our expressions of that which is purely intelligible … We pass not merely into brevity of speech, but even into absolute silence, of thoughts as well as of words… . We mount upwards from below to that which is the highest, and according to the degree of transcendence, our speech is restrained until, the entire ascent being accomplished, we become wholly voiceless, in as much as we are absorbed in Him who is totally ineffable.

So the answer to my headline’s question is: Yes. If a mystic is someone who has been transformed by mystical experiences, then Wittgenstein was a mystic, who was exceptionally eloquent, in his own gnomic way, at expressing the inexpressible. I’ll give him the last word. He concludes Tractatus with this mystical passage:

My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.) He must surmount these propositions; then he sees the world rightly. Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent.